Structured learning and unstructured learning are equally important

I was teaching a lesson recently with an advanced student. He's played his whole life, but only recently started the in depth study of jazz guitar and jazz improvisation. In analyzing what had been changing for the better about his playing, he also pointed out that flowing improvisational phrases were still escaping him. 'Going through the motions' was not his choice of words, but let's just call it that for lack of a better term (and memory, on my part).

At a young age, I learned what improvisation was, and was absolutely fascinated by it. I couldn't get my head wrapped around how one scale (the blues scale) was so widespread throughout American music, and so many players were able to create so much with it at a moment's notice. I learned as many of their guitar solos as I could, and I tried to do my best at improvising with it too.

I spent a good number of hours noodling, as many players call it. Playing with no intent beyond creating sounds and exploring the instrument. I think that it's (within reason) one of the most important things a player can do. Here's why:

1.) You apply the vocabulary you've learned

I have said for decades, and I'm by no means the first to say so, that music is a language. In learning a foreign language, one memorizes basic phrases: 'hello, how are you?', 'where is the restroom?', or 'I'm from Florida, please don't hold that against me'. One learns things like the syntax of that language and the conjugation of verbs, so one can create their own phrases. If you are fluent in English, you can ask where the restroom is in ways ranging from something you'd say at thanksgiving dinner with your grandmother sitting next to you, versus something you'd say on a Friday night out in a bar with your friends.

Music works that same way. You learn the syntax, the phrasing, so you can clearly express yourself with it.

2.) How can you play to changes if you can't play when there's no changes?

Jazz is arguably the most difficult style of music to learn how to play. One of the aspects of that difficulty is creating melodies, on the spot, for songs that don't stay in one key. So, how is one supposed to improvise a melody on difficult chord changes if a simple melody cannot be improvised on something diatonic? That's where the noodling comes in.

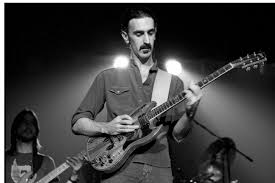

"Jazz isn't dead, it just smells funny"-- Frank Zappa

There are so many jazz musicians who can't improvise on a one-chord funk groove. They need the structure of something to play to, and are often just as lost playing on one chord as a rock guitarist is while playing “Autumn Leaves”. They've always had structure, and are lost without it. What makes matters worse is they'll often condescend any style of music that does not involve improvisation to chord changes with a swing feel.

3.) Noodling = improvisation = composition

There are certainly many ways to approach writing a song, I have another blog post about that. One could argue a huge part of writing for your instrument is to improvise, and remember what you improvised upon playing something that you like.

Being creative is a huge part of why all of us have taken up an instrument, and this is the culmination of all that training. Take the music you've been learning about and create your own music.

There is a caveat…

4.) Noodling should not be all that you do

Frank Zappa has a quote mentioning how there's good and bad noodling. Something to the point of when you're playing your instrument, you should always play with purpose and conviction. But even purpose and conviction can take you so far.

Balance in life is key, as is with playing music. As important as it is to create your own melodies, it is equally important to learn the melodies of others. It's important to put a recording on and learn them by ear, as much as it's important to sit down and count it out and learn it from a piece of paper. It's also important to maintain those melodies which you've already learned.

Effective practice sessions should have all three of these aspects-- the structure of learning new things, the structure of maintaining what you know/can play, and a lack of structure so you can use those ideas to create your own. By all means, noodle away. But don't forget to learn what other people have noodled, or forget their noodles that you have already learned.

Adam Douglass has been playing guitar for 25 years and teaching for a good 20. He currently resides in Brooklyn, New York where he is an instructor; and plays with his band doing his original music, jazz standards, or whatever other gigs might come his way. His guitar of choice is the Fender Stratocaster, though if money were no object he'd have 3 or 4 of everything. He prefers tube screamer-like overdrives and clean boosts, with touch of analog delay. Hit him up at info@adamdouglass.com, as he is always happy to discuss interesting topics.

Get noodly, but don't get soupy.